Earlier this summer, I wrote that backcountry outings are non-negotiable parts of my life. It is essential to surround myself with the threatened landscapes that I write about and to experience joy as an antidote to despair. It is the fuel to keep floating into such daunting waters. This holds ever true.

Though it may appear that I am always wandering the desert, mountains, and rivers, I spend much of my time writing. And a lot of that time is on the phone, talking to legal experts, Tribal leaders, scientists, and environmental thought leaders.

Freelance writing is a juggling act. Distributing assignment loads manageably is an act of alchemy, faith, advocating for myself, and thoughtful editors. Still, I am amazed when several months of work are published all at once in a monsoon-like deluge. A reminder to trust nature, not deadlines.

Trump Administration Sets Stage for Attack on National Monuments

The recent Department of Justice (DOJ) opinion about national monuments has been buried amid the uproar over Senator Lee’s canceled public land sale proposal and the big F***** up Bill now signed into law. This administration’s DOJ rewrites a 90-year legal interpretation of the Antiquities Act that makes public lands advocates wary as the admin reviews 6 monuments. However, history reveals the cracks in this scheme to downsize or outright dismantle monuments. For Sierra Magazine.

Despite the legal jargon this story navigates, the land needs to be given a voice. I had the honor of speaking with Donald Medard, a Fort Yuma Quechan Tribal member and outreach specialist, about Chuckwalla National Monument in Southeastern California. He told me, "People drive I-10 and they just see a desert," but Chuckwalla National Monument is "more than meets the eye."

The 740,000-acre monument protects an iconic southeastern California landscape and connects two of America’s iconic desert ecosystems—the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. Descending from 4,500 feet above sea level to 50 feet, the landscape is rich with biodiversity and protects a wildlife corridor for the endangered Agassiz’s desert tortoise and the desert pupfish. Some of the monument's native plants, like the Mecca aster, Orocopia sage, and Munz’s cholla, grow nowhere else on Earth.

The national monument honors and protects the home of 13 tribal nations, including the present-day Cahuilla, Chemehuevi, Mohave, Quechan, and Serrano Indian tribes. Medard explained, "[Chuckwalla] is a place where we as a people have thrived since the beginning of time. For us, it's not only a place of history, but a place for our future generations to learn more about what it truly means to be Quechan."

As a kid, I looked out the window of my parents’ station wagon on I-10 and saw a desert. Though we never ventured very far off the main drag, just by seeing such a vast, undeveloped landscape (by present standards), I was consumed by wonder. Curiosity and mystery were the gateway drugs that opened the portal to the life I live now. Mine was not a childhood of backpacking trips. It was one of sleeping under the stars in a suburban backyard, voraciously reading books, and dreaming of future explorations. And that, in many ways, is just as formative.

I share this because the point of protecting and preserving landscapes is not only about recreating and seeing every inch of them. This is what Stegner meant when he wrote,

“These are some of the things wilderness can do for us. That is the reason we need to put into effect, for its preservation, some other principle than the principles of exploitation or “usefulness” or even recreation. We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope.

How these lands are managed for future generations and by whom also matters a great deal. In 2022, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition (BEITC) signed a historic agreement to jointly manage the monument with the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service. This legally binding agreement remains in effect regardless of the monument's status.

Tribes affiliated with Chuckwalla National Monument are in the process of forming an official tribal coalition. Medard said the Trump administration's actions may "slow the process and may discourage conversation between the tribes and BLM to develop stewardship documents," but it does not impede their efforts to move forward.

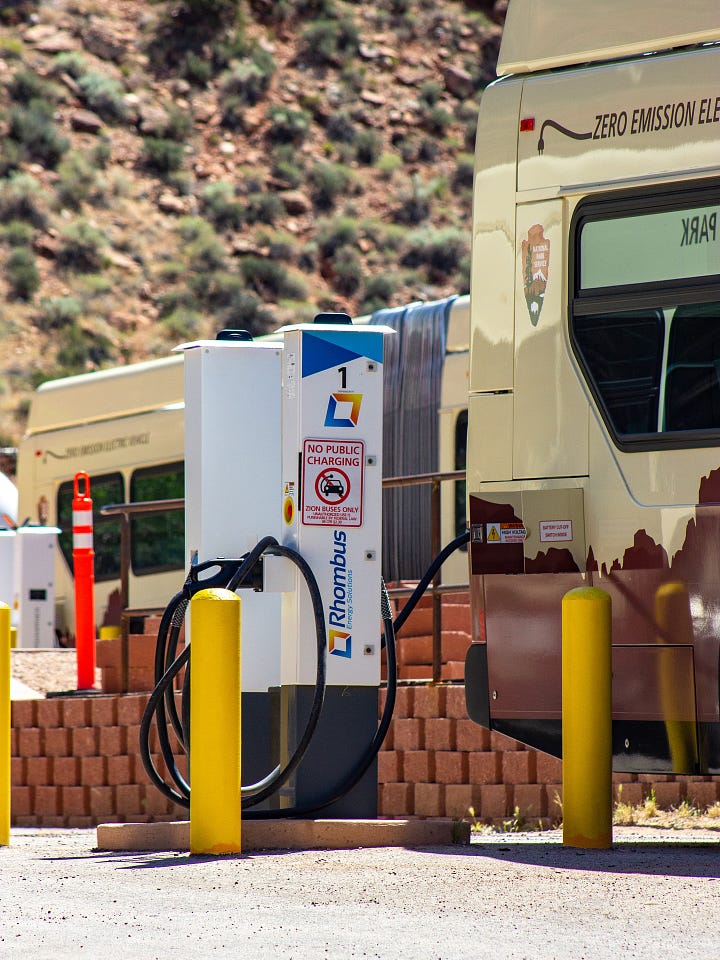

Zion National Park Clears the Air

Remember that time I went to Zion National Park to look at electric buses? This is why:

It is a challenging time to write about public lands. The task of reporting on positive news is also daunting but critical. It forces you to consider this moment in history with more nuance than our enraged hearts would like to face sometimes.

Yes, there are still good things happening. And there is much pressure to complete important projects before more funding is cut. The work being done to improve protections for the natural world needs to be celebrated.

In Zion, the completion of an all-electric shuttle fleet is not only mitigating traffic in the second most-visited National Park, but it’s also bringing back the wildlife to Zion Canyon. For Reasons to be Cheerful.

Summer Reading

I am diving into The Way Around by Nicholas Triolo, an ultra runner turned walking philosophical aesthetic.

Growing up in northern California, in a family of high-achieving athletes, Nicholas Triolo was imbued with a particularly acute form of our intensely goal-oriented culture. “Do the reps,” he internalized. “Commit to the work. Grind for your dreams.” Shortly after graduating from college, he embarked on a solo circumnavigation of the globe. And then after returning to the States, he threw himself into ultrarunning, all to combat a deepening discontent.

While traveling around the world, it was in Kathmandu that Triolo first encountered kora, a form of moving prayer in which pilgrims walk in circles around a sacred site or object—a kind of “ritualized remembering” birthed by place. Unable to shake this initial encounter with circumambulation, he sets out here on three such extended walks. First, he completes the sacred thirty-two-mile revolution around Tibet’s Mount Kailash, in search of a cultural counter to Western linearity. Then, following his mother’s diagnosis with breast cancer, he returns home to California and takes part in an annual circuit of Mount Tamalpais, tracing a route made famous by Beat poets Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Allen Ginsberg. And then finally, he meets up with a quirky hydrogeologist in Butte, Montana, and joins his walk around the Berkeley Pit Complex, the largest Superfund site in the country.

At once uncommonly humble and thrillingly transcendent, blurring the boundaries of inner and outer landscapes, The Way Around models what it means to experience a true revolution of heart and home—for the flourishing of all.

As a former competitive athlete, who liberated the reins through yogic philosophy and desert wandering, this book resonates deeply. It delves into important considerations for all of us living within this hypercapitalized colonizer system of achievement.

The writing is gorgeous, and the storytelling makes it hard to put down. I already don’t want this book to end. Congrats, Nicholas! (Buy the book and subscribe to his Substack, The Jasmine Dialogues.)

That’s enough screen time for now! Hope you can run away from yours for a bit too!

🧡

Morgan