“Morgan, maybe you can take on the Bernheimer Expeditions one of these days. It was a series of pack train treks across parts of the canyon country by a wealthy New York guy—Charles Bernheimer . . . Like other members of the elite who wanted to explore unknown lands, he depended on local Navajos, Paiutes, cowboys, and guides like John Wetherill, who lived year-round in the mysterious places and referred to them as home.”

Within this email from archaeologist William D. Lipe, or Bill, dated February 2019, were the keys to a new direction in my life. I was already at the crossroads, living at the junction of remote southern Utah canyons in winter. It’s not that I needed someone to prod me to retrace thousands of miles of historic expeditions. It’s that living alone, with no one around, Lipe told me that doing so mattered beyond a personal adventure. At the end of his email, Lipe lamented, “Too bad there’s so much snow out. I’d like to follow some of Bernheimer’s routes too.”

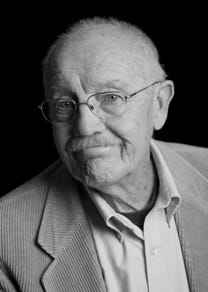

Lipe was at the time one of the great still-living Southwest archaeologists. His area of study, spanning Glen Canyon and Bears Ears to Southwest Colorado, went beyond contributing to the study of early Indigenous people living within these areas. Lipe shifted the compass with regard to methods of archaeological study, advocated for the inclusion of women in the field, and was assertive about the necessity of the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives. In Ancient Tracks, a 2006 tribute to his career, he said:

It’s essential for archaeologists to keep working on trying to find common ground with Native American groups. I think it’s important morally and ethically because of the history that we all understand—both the larger history of oppression of Native Americans, and the marginalization of living peoples in the way archaeology was conducted for so many years . . . It’s politically important because the tribes, in fact, can have a large effect on what does or doesn’t get done in archaeology, and, of course, the tribes employ lots of archaeologists and are part of the system in that sense. Intellectually, I think it’s been of great value to archaeologists to have to examine implicit premises about what’s important, and how to present the history of traditions and history of a people who are not in the same historical tradition that we come out of.

In the latter stages of his career, Lipe’s efforts shifted to conservation archaeology, specifically on Cedar Mesa, and supporting efforts to protect Bears Ears National Monument.

I first wrote a short matter-of-fact email to Lipe with a research question in 2018. Archaeology Southwest editor Kate Sarther and archaeologist/author R.E. (Ralph) Burrillo both encouraged me to reach out to him. So it is fitting that I woke up to a message from Ralph, letting me know about Bill’s passing. His Archaeology Southwest memorial essay contextualizes the force Lipe’s life brought to monumental events in the Four Corners over the last 50 years.

Lipe was 89 and lived a full life. In our final emails to each other, he mentioned slowing down amid a procession of information and thoughtful questions that hinted at anything but.

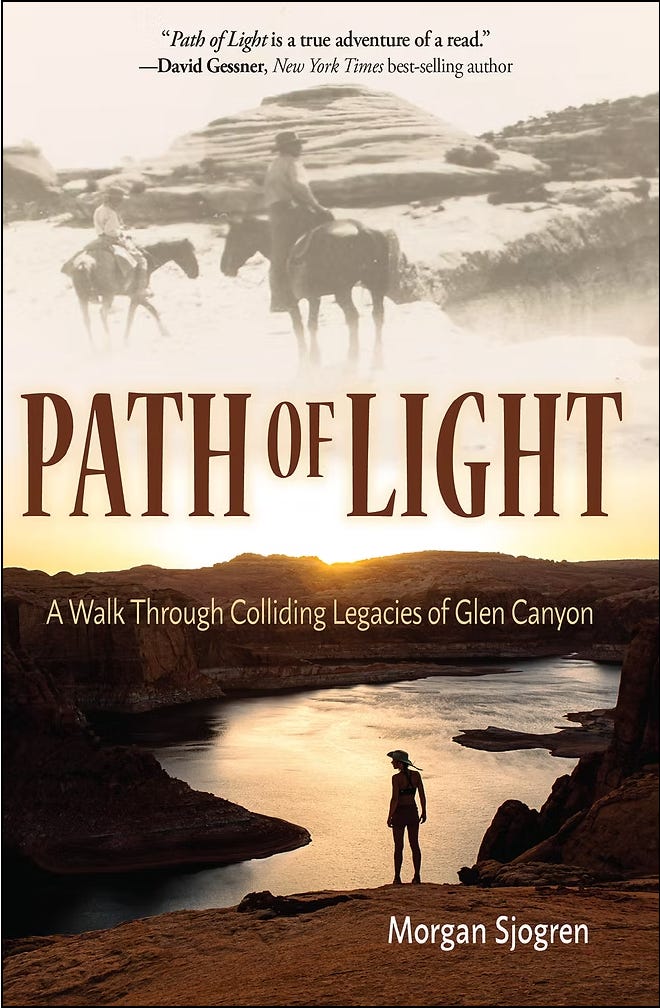

With Lipe gone, there is an immediate void in my life. And yet, within our letters, are a lasting record embedded with layers of wisdom and good cheer that will carry me onward on this most unusual path. Sifting through the pages of correspondence, which could fill a slim book, I find myself smiling at Bill’s quips and revisiting old exploration flames that ended up on the backburner while I quested alongside Charles L. Bernheimer to write Path of Light.

Lipe’s emails always included his trademark treasure trove of anecdotes, photos, and sources. These did far more than assist me with what I was writing, they opened the synapses of my canyon mind to explore new story possibilities. Lipe was generous like that. He never refrained from sharing a perspective, contact, source, edit, critique, and genuine praise and encouragement.

In one of my favorite emails, Lipe cautioned against the pursuit of “adventure” which, according to his mentor Jesse Jennings, “only happen to people who don't know what they are doing." He continued in his letter, “Still, we all succumb to the excitement of exploration and the possibility of adventure (at least until it becomes life-threatening...).”

Lipe and I never met each other. (Ralph should never let me live down missing the opportunity to drink wine with Lipe at Celebrate Cedar Mesa in 2020.) Instead, I was out exploring in the canyons. Lipe wrote that he understood––after all, this is what truly fueled our extensive emailing spanning six years. While trading stories about Glen Canyon and Cedar Mesa, he described these areas as his “home place” in archaeology and as a human being.

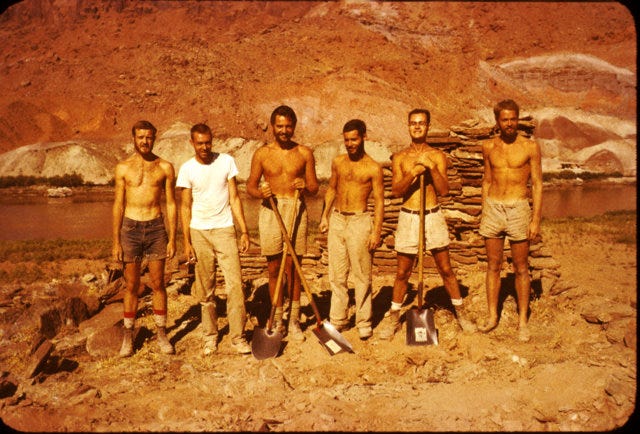

The first email I sent Lipe was about the Glen Canyon Project, an effort in the late 1950s and early 1960s to survey the ancestral and historical sites to be flooded by Glen Canyon Dam. In all, 186 miles of canyon and cultural landscape were inundated. During dam construction, the Glen Canyon Project rapidly surveyed and excavated 2,000 ancestral sites up to and beyond the flood zone. These items were collected and transferred to museum and university archives. The study also focused on a broad attempt to better understand the habitation and material culture of the area.

Lipe was a crew chief in his twenties when he spent three summers in Glen Canyon watching the Colorado River get dammed. Of this, he wrote to me:

I was born in 1935 and grew up at a time when the country was coming out of the Great Depression and then surviving World War II and was devoted to “progress” defined as building bigger buildings, bigger businesses, bigger highways, etc.—and bigger dams on major river systems. Most of us on the Glen Canyon Project thought it was a shame that such amazing places as Glen Canyon would go underwater, but we just accepted that as the way things were supposed to be. If you had a river, you could expect a dam. It wasn’t until people began to fight for saving special places that the national consciousness began to change, and mine changed with it. The battles to keep dams from backing water up into the lower Grand Canyon helped turn me and many others into active environmentalists. But those changes took hold with most of us in the early 1960s, after our time in the Glen and after the dam was closed in 1962.

It’s unsurprising that after experiencing such loss, Lipe often sent me old photos of Glen Canyon in the sixties for me to locate, match up, and recreate on my explorations. He cared about these places and wanted to see how they were doing. Frequently, we both came up relieved that despite the popularity of the desert, some places were still protected by being off the radar––and looked over lovingly by generations of people willing to walk long distances and perhaps, learn a bit about their history.

With Lipe’s blessing, much of our correspondence and his shared knowledge is time capsuled in Path of Light. I thought of him as my Charlie (as in Charlie’s Angels) for the way he seemed to email me at the right time with a new detail, lead, or old map. The time he spent fact-checking and editing ensured the book had solid legs to share explorations of canyon country with readers.

Lipe’s contributions to American archaeology are massive, and I do not doubt that a slurry of archaeologists could dedicate an anthology in his honor and still not fully scratch the breadth of his contributions. I look forward to reading what surfaces.

After POL’s publication, Lipe and I continued to email, albeit not as frequently. It’s fitting that our last letter focused on warm gratitude and support toward one another. I treasure how through the consistent act of written correspondence, Lipe became a trusted mentor and dear friend.

More than any fact, theory, obscure desert route, or significant cultural site, true relationships and exchange of ideas are what I have come to value most through the work labeled as “writing” and “exploration.” Lipe continues to inspire me to spend intimate time in the places I consider “my heart’s home,” while writing and advocating for their care and protection. His memory also spurs me to stay in contact with other mentors, elders, and visionaries willing to sit down and take the time to write an old-fashioned, or new-fangled, letter. To create a better future, we need relationships that span generations.

For those interested in learning more about Bill Lipe and his work in Glen Canyon:

In 2014, Lipe edited “Torturous and Fantastic,” for Archaeology Southwest celebrating greater Cedar Mesa’s archaeological record and thousands of years of human innovation, change, and movement. This was among the first printed materials about the region I ever got my dusty hands on. For the 2018 issue about the area now known as Bears Ears National Monument, Lipe contributed an essay but passed the editorial torch onto R.E. Burrillo and Ben A. Bellorado.

If a book about your life and career is written while you are still alive, it is kind of a big deal. Ancient Tracks by R.G. Matson and Timothy A. Kohler did just that in 2006. I bought a used copy and it is a treasured part of my desert rat library.

Path of Light––A Walk Through Colliding Legacies of Glen Canyon includes a heavy dose of stories and perspectives from Lipe. In retrospect, this book is as much about retracing many of Lipe’s footsteps across Glen Canyon as it is about explorer Charles L. Bernheimer.

Behind the Bears Ears by R.E. Burrillo is brimming with Lipe-isms and stories from his work on the Cedar Mesa Project. Burrillo carries Bill’s torch in being an archaeologist who also cares about public education and talking about archaeology in a deeply intellectual yet people-friendly way. Not to mention encouraging non-archaeologists, including myself, to learn and write about the field.

The Glen Canyon Country by Don Fowler is the authoritative Glen Canyon history book written by a Glen Canyon Project crew member who worked with Bill (far left, Don is to his right). My copy is ear-marked, water-damaged, and very loved.

This video from the Verde Valley Archaeological Society is a true gem that many of us desert rats hopelessly lost in a love affair with Glen Canyon watch again and again.

Very lovely, Morgan. Thank you for doing this.

What a blast from the past hour watching that video! Thanks for posting it, Morgan. I didn’t know Bill personally, but he was still heading Archaeology Southwest when I was a member. And what a great read/study his Torturous and Fantastic was. It was so big in my life; I spent every morning for quite awhile pouring over it with coffee, lost in beauty and making future plans. A great, great man and bright light went out of the world when Bill died.