I planned to be boating the Grand Canyon this week with an amazing cohort of creatives. Instead, I am rafting the couch with Covid. With my offline plans thwarted, I am here where the headlines are decidedly dark with all manner of soot.

This week, an executive order claims the U.S. is ready to bring back “beautiful clean coal.” The catchphrase is an immediate head-scratcher for anyone who fretted as a kid about getting a lump of coal in their stocking. Environmentalists and Indigenous activists have long fought against the well-documented and proven health hazards associated with mining, processing, and burning coal. Energy and economically minded folks have recognized that coal is on the way out, with the investment and transition to renewables successfully underway.

Resurrecting coal along with a new myth that it is suddenly clean energy is mind-boggling, but maybe not so shocking in a week that saw Tariffs plummet the stock market, only for a 90-day pause to raise financial spirits from the dead overnight. Tied into this coal-fired revival, is the idea of a resurgence of mining and manufacturing jobs in the U.S. This, without recognizing the government subsidies that once made any of that possible––from the price of minerals to health care to infrastructure in rural communities. And unions. So basically, the antithesis of what the people promoting coal stand for. The goal of coal is to create energy to meet the power demands for the growth of energy centers, ai, and electric vehicles.

I shudder when I let my imagination drift into sci-fi mode, envisioning the future these people have in mind for the rural West. Perhaps I will be sitting outside in the desert, under a warm plume of smoke. I will be reading an e-book written by ai, that was trained by stealing one of my books. I look up from my screen toward a nearby open pit mine––once a massive wild mesa strewn with sagebrush, pinyon, and juniper trees. The book interrupts my daydreaming to let me know that my partner will be back from work at the mine in an hour and that the book needs to be plugged in. Our human lives now revolve around charging, and extracting energy, to keep the bots that run our lives going.

I pick up a hammer and smash the e-book.

It is not clear that any of this is supposed to make sense. So rather than wrack my brain around any assessment of future absurdity, I am revisiting things already well known. Right now, it feels especially important to anchor ourselves in reality and history. Events from even 5 years ago are easily forgotten in such volatile political conditions.

The resurrection of coal in the headlines brings me back to a piece I wrote at the end of 2020.1 A dark year, to capstone four, in which the demolition of the largest coal-fired power plant in the West brought me immense hope. It still does, perhaps more so today.

Demolishing Coal

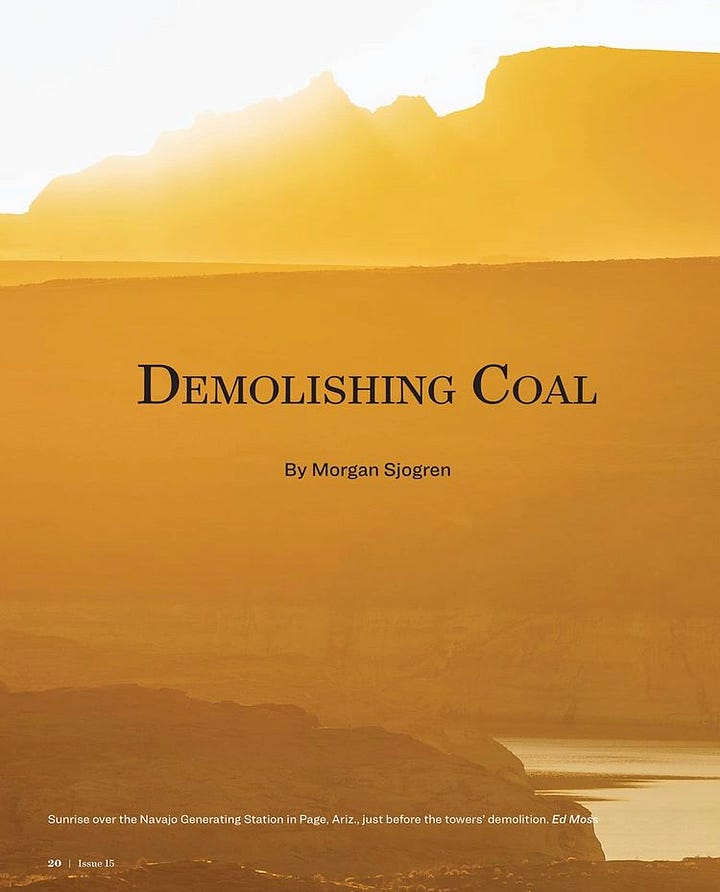

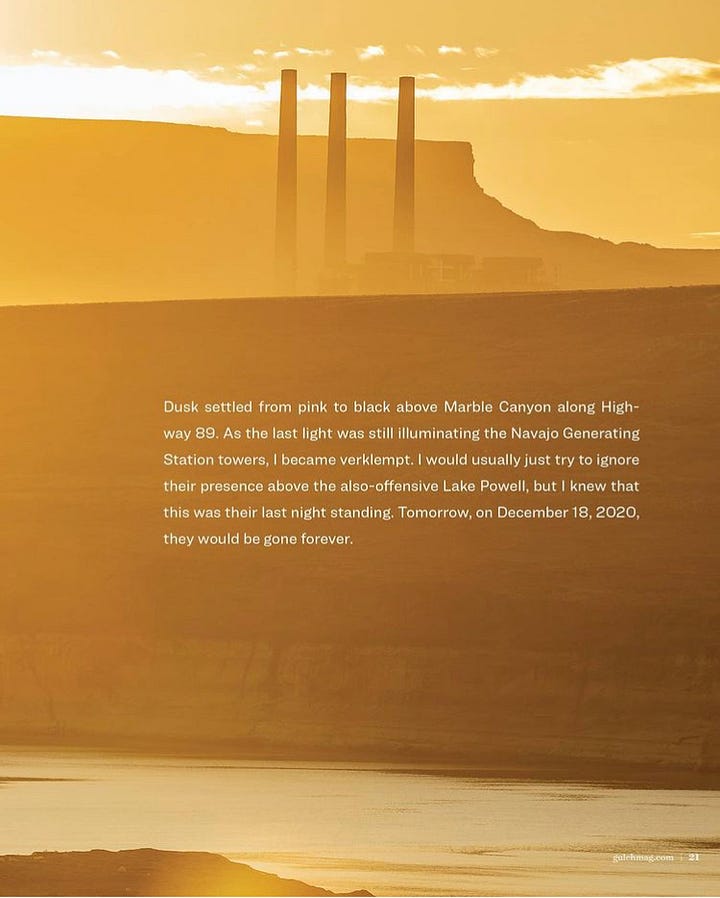

Dusk settles from pink to black, with last light still illuminating the Navajo Generating Station towers that loom over Page, Arizona. Above the station's three prominent, identical 775-foot-tall flue gas stacks, exhaust plumes remains a fixture in the skylin.2 A dreadful sight next to the equally offensive Lake Powell. Expecting to feel rage, this evening I am joyfully verklempt. Tomorrow––December 18, 2020––they will be gone forever.

Following Glen Canyon Dam's completion in 1963, the NGS plant was built just miles from the new reservoir in 1974 to power the Central Arizona Project. The 336-mile system transports Colorado River water to Arizona’s major cities, Phoenix and Tucson, and Tribes. The water spurred agricultural growth and suburban development in one of the driest states in the nation.

Large amounts of electricity would be necessary to move the water from Lake Havasu Reservoir across the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. After public outcry, the NGS plant was chosen instead of constructing Bridge Canyon and Marble Canyon hydropower dams which would have flooded portions of the Grand Canyon. The electricity generated went to a pumping station at Lake Havasu to deploy the south-bound water diversion.

The additional power generated by NGS was distributed as far away as Los Angeles, California. The sad irony is that NGS failed to power 15,000 homes in the neighboring Navajo Nation where 10% of people don’t have electricity. This was just one of the resulting injustices.

Strip-mined coal for NGS was transported by rail 80 miles from the Peabody Kayenta Coal Mine on Black Mesa, within the Hopi and Diné homelands. Additional coal was transported further still to Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada. Water from deep within the ancient aquifer beneath Black Mesa was pumped to slurry the coal. Black Mesa is a sacred landform in both the Diné and Hopi cultures. But, human administrative decisions do not always align with cultural values.

In his book, A Pagan Polemic, aural historian Jack Loeffler recounts discussions with traditional Hopis and elders upon learning about the Peabody Coal Mine: “All sixty-three Hopis rose as a single body, each of them enraged, especially at their Tribal Council for selling out a sacred landform.”3 After discussion, the group began forming the Black Mesa Defense Fund to inform the American public about this travesty.

NGS's toxic legacy affected lives, health, and the environment of the surrounding communities. According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, "The Navajo Generating Station consistently ranked as one of the top 10 sources of carbon pollution in the U.S., belching out 8.6 million tons of carbon dioxide annually as well as heavy metals and other pollutants." The Clean Air Task Force, an independent environmental advocacy group, reported that NGS emissions contributed to health problems ranging from asthma to heart attacks. Both NGS and the Kayenta Coal mine are also known to have impacted nearby groundwater. Cases of black lung continue to emerge on the Navajo Nation among former coal miners.

To watch the three massive towers come down via explosives early tomorrow morning, I head to the Wahweap Marina RV campground. There to celebrate the occasion with me is my friend Ed Moss, a photographer and environmentalist who hates dams, uranium mines, and coal plants as much as I do. Though we acknowledge the irony of staying at a highly developed site with RV plug-ins and heated bathrooms, the place is a perfect vantage point to view the towers' demise.

When I arrive, Ed is already there waiting, with two open bottles of cheap red wine—one for each of us. Temperatures plunge below freezing after the sun sets. To stay warm, we keep a fire burning, piling on tumbleweeds to keep it crackling. The wine helps, too. Too excited to sleep, we briefly nap at 5 am before the show starts.

At dawn, we migrate to an overlook above the western shore of Lake Powell, centered upon sweeping views of Navajo Mountain, Cummings Mesa, Wahweap Creek, and the Glen Canyon Dam. While crowds of people crowded the view of NGS on the other side of town, we were positioned far from the masses for the view that we specifically craved—the release of the Glen Canyon skyline from captivity.

With frozen fingers, I sip coffee as the sun rises for the final time above the towers. The towers are scheduled to fall between 8:00 and 8:45 am. I risk permanent damage to my retinas by occasionally staring straight into the sun, so I don't miss the event.

Ed is fiddling with his telephoto lens when the skyline shifts, "Oh shit, Mo, open your eyes, it's happening!"

A faint billow of smoke emerges from the left tower as it begins to lean. The plumes expand from the base as the tower tips, slowly at first, before picking up speed and collapsing. From our distance, there is a delay in the sound of the massive boom reaching us. We hear the wreckage of tower number one as number two begins its descent. My body is frozen, but my emotions join the explosions. "Fuck Yeah!" I cheer from deep in my belly as tears stream down my face. Ed is thoroughly entranced, unable even to blink while muttering, "Oh fuck. I'm shaking. I'm crying." After the third tower falls, there is an abrupt shift to silence. Only smoke and debris fill the void where the towers once dominated the skyline.

We remain still in reverence, but we are not satisfied. The scene has fueled our Monkey Wrench Gang fantasies to a maximum. With the towers gone, we gaze at the Glen Canyon Dam. Now, it's possible to imagine the dam's removal in our lifetime.

A few miles up canyon from last night's campsite situated well above the flooded mouth of a tributary of Glen Canyon and Lake Powell, another set of towers still stand proud. Thin straws of virgin white Entrada Sandstone are topped with crowns of colorful conglomerate rock. The tallest among them is known as the Tower of Silence. Its base appears as if white wings folded around itself in a loving embrace.

Though hidden deep in a secluded nook, the hoodoos stand within a portion of Grand Staircase-Escalante, removed from the original monument boundaries, an irreplaceable landscape threatened by the coal industry's hold on the region. The prospect of coal extraction in Grand Staircase is hyper-focused on the mesa looming above, which is rich with natural coal seams. Burning hills that vent plumes of steam from underground remind us that this landform is not merely a resource but also a living thing. This culturally dense 50-mile-long mesa sits at 7,500 feet, straddling the Canyons of Escalante and Glen Canyon, directly across from its coal-burning nemesis, the Navajo Generating Station, which will burn no more.

Though the preservation of wild places is a never-ending pursuit, watching the NGS towers vanish is a sigh of relief for this landscape. Coal has fallen in Glen Canyon and the Grand Staircase. The Tower of Silence has spoken. Nature has outlasted this failed attempt by man to conquer it. With the explosive removal of these blights from the horizon, their void shines as a beacon toward a future built on sustainable practices and renewable energy. While the jagged mesas hover in the distance, crowned by the sun and a plume of smoke from a funeral pyre, a small piece of Glen Canyon is free.

Postscript: After the fall of the towers, then-Navajo Nation President Jason Nez, acknowledged that NGS going offline resulted in at least 1,000 lost jobs and a $30 to $50 million economic loss in the 2020 fiscal year. Yet Nez shared his optimism for renewable energy and a sustainable economic future built upon one of the area's dominant resources—sunshine. He commented in a Tucson.com op-ed, "We see great potential to become a leader in the development of renewable energy projects." Arizona Public Service, the state's largest utility, pledged $144 million to the tribe and agreed to buy power from future Navajo Nation clean energy projects. The Arizona Corporation Commission also approved $475,000 in annual funding to help Navajo and Hopi communities shift to energy-efficient projects. The Central Arizona Project also followed suit, diversifying its energy portfolio focused on hydro and solar power.

This week, current Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren welcomed the return of Coal. In a social media post featuring a selfie with the U.S. President, he wrote:

“Today marks a pivotal moment for energy policy in the United States. As President Trump signs an executive order aimed at revitalizing the coal industry, I want to emphasize the importance of including tribal nations like the Navajo Nation in this national conversation.

In 2024, the Navajo Transitional Energy Company (NTEC) was the third-largest producer of coal in the United States. That same year, the International Energy Agency reported a record-breaking global demand for coal. As global electricity demand continues to surge, we are proud that NTEC and the Navajo Nation are part of this narrative—providing critical resources to support energy security at home and abroad.

The harmful policies of the past have unfairly targeted coal, but those tides are turning. Last year, the U.S. produced over 1 billion tons of coal, and even now, we are producing more than 500 million tons annually. If the federal government is serious about increasing domestic energy production, enhancing permitting, and bolstering energy security, it must work in partnership with tribal nations. For the Navajo Nation, coal is more than an export—it has powered our homes and our economy since the mid-20th century. Our people have depended on the royalties, wages, and tax revenues from this industry for generations.

As we plan for a just energy transition, the transformation of the former Navajo Generating Station—once a 2.25-gigawatt coal-fired power plant—into a campus for housing development is a powerful example of how communities can reimagine their futures. Shutting down NGS too soon cost us hundreds of jobs and revenue streams – approximately 3,000 in direct and indirect jobs and $40 million per year. The Navajo Nation is ready to lead—not only in energy production but in shaping an energy future that honors our sovereignty, strengthens our economy, and secures our place in the global supply chain.”

The comments that follow from members of the Navajo Nation are an important read that highlights the personal injustices, health harms, and environmental concerns negated by these directives at all levels.

These voices need to reverberate, not just in the Four Corners Region, but across the country, where the toxic legacy of fucking dirty coal will continue to harm us all.

It’s frustrating to see positive steps taken forward, only for swift reversals with administrative changes. With each shift, grave damage is inflicted on the environment and the humans that are part of nature. But we’ve seen what a policy and investment turnaround can accomplish. We all now know what life before and after the decline of coal is like. The changes are visible across the clear skies of the Four Corners where half of the region’s coal-fired plants have gone offline in the last decade+.

Beyond environmental concerns, economics have been the demise of coal in the past. If the current economic landscape offers any hints right now, it is that high levels of uncertainty make the stakes of gambling on anything too high. Even planning for business as usual. And coal, long knocked off its pedestal, is a gamble. Not that anything doled out by this administration is not.

All of this is head-spinning amid so much going on right now. But if one thing is certain, this is a time to remember and to remind our representatives, about our right to human health, investments in clean air and water, and the pursuit of industry that builds communities without killing them. The blank spot across the Glen Canyon skyline is a potent reminder.

In 2019, the NGS plant was decommissioned. This story originally appeared in a spring 2021 issue of The Gulch, a now-defunct Four Corners-based publication. Minor edits and additions have been made to keep up with the times.

This article breaks down the financials, but its statement that the energy produced was safe is misleading and does not count any of the health and environmental hazards: https://media.srpnet.com/navajo-generating-station-permanently-shuts-down/

https://ieefa.org/media/536/download?attachment

Loeffler, Jack. A Pagan Polemic: Reflections on Nature, Consciousness, and Anarchism. United States, University of New Mexico Press, 2023, p. 111. https://www.unmpress.com/9780826365170/a-pagan-polemic/

Great piece! I’ve lived in Sedona for thirty years and have spent a lot of time exploring the Colorado Plateau, my homeland. Though I didn’t see the smokestacks fall, I rejoice every time I head up to Page and beyond and I don’t see them.

Now if only we could get rid of the dam…

An awesome, beautiful and wonderfully defiant essay: I think Katie Lee and Bonnie Abbzug would appreciate your sentiment. We need a little moxie in these weird, uncertain times, and we also need to listen to the tribes, to the earth itself.

Keep up the great work and enjoy the canyon country.